OTR, Take 23: Big Red Machine - How Long Do You Think It's Gonna Last?

To listen as you read, click here.

Hello hello and happy Saturday!

Can I get a show of hands for introverts in the group who can appear extroverted for short bursts? Enough that most people wouldn't think of you as introverted? Okay, hello fam!

Now imagine having to put on that mask for nine days straight, for most of each of those days. Yes, I see you crawling back into bed and pulling the covers over your head. That's how I feel this morning, too.

(For the extroverts in the room: it's funny how much introverts know and understand about extroverts – after all, the world is built by and for extroverts – and how little extroverts comprehend introverts. One very quick and easy way to make a big difference in your team's lives is to learn about introversion and introduce new work modalities that empower the introverts on your team.)

I'm usually pretty good about pacing my social obligations, permitting myself sufficient downtime to recharge and play with this little clown.

This past week was just a conflagration of obligations, opportunities, and chance that required me to be On...all week. So this morning, after a short jaunt with Clare, I decided to listen to something a bit more relaxing, one of my favorite records from last year.

"How long do you think it's gonna last?"

I love this phrase because it can take on so many hues depending on the context. The magic of a shooting star. A fever that accompanies the flu. Those wondrous pangs of young love and the poise of established love. Life.

How long do you think it's gonna last?

I've been thinking a lot about time, and the illusion of time, lately. (Language, inherently in tense, fails me in this endeavor.)

One of the things that I've been returning to somewhat obsessively, is the feeling of impatience so many of us feel at reaching or achieving the notion we have of ourselves. Allow me to tease out that thought, because it's not obvious (or poorly stated – or both). I have often felt that I am on a quest to "reach my potential" – some version of myself that my pea brain has decided is some true, authentic, and optimal version of me. I know that I am not alone in this: I think to some extent most of us feel this way.

With this notion of the self that we ought to be, it becomes almost inevitable that we are disappointed in the person we presently are. One potential reaction to this is that we will work toward achieving the things we associate with how we want to see ourselves, that we strive toward actually cutting the figure in the world we imagine we should cut. (Another, sadly common, reaction to this is a quest for self-abnegation: substance abuse, self-sabotage, self-loathing, etc.)

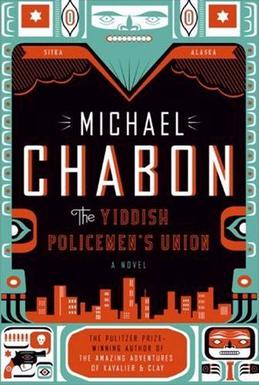

I was introduced to the concept of the Tzadik ha-Dor by Michael Chabon's The Yiddish Policeman's Union. In Judiasm, there's the promise of a messiah who will arrive to redeem the Jewish people. (This is the messiah Jesus claimed to be.) In some strains of Judaism, there's the idea that there's a potential messiah born in every generation. That there's always a potential messiah walking the earth: this is the Tzadik ha-Dor.

The idea is that the Tzadik ha-Dor is born with all of the qualities needed for a messiah, but will only be called to serve when the historical circumstances line up properly. So there's a potential messiah failing to reach his potential on a perpetual loop, at least until it's time for the Messiah to emerge.

I've come to think about "living up to potential" in terms of the Tzadik ha-Dor: we all innately recognize the potential within us, yearn for it, and often burn ourselves out in the pursuit of it. (The Tzadik ha-Dor in The Yiddish Policeman's Union winds up a supremely talented drug addict who is murdered at the beginning of the book.) What I've begun thinking is that we're preternaturally gifted at projecting different potential selves and that our sense of being lost in time – wishing we could just grow up as kids, lusting after having finally "made it," desperately wanting to return to halcyon days – is the displacement of these potential selves from our current selves.

Our imaginations are profligate, but our reality stubbornly insists on permitting us to experience only one timeline.

How long do you think it's gonna last?

The thing about building things is that it is the only way we can actively try to control our timelines. (I suppose breaking things also counts: the key is taking active responsibility for the shape of what's to come.) Building things is hard work. Building things that provide consistent meaning and good vibes to both you and your people is very hard.

For a long time, I didn't take on these projects. A part of me felt that these things were created by Great People, and that I need not apply. Then I started meeting and getting to know some heroes of mine, and let me tell you: your heroes are just as fucked as you are. They've just decided to do the thing anyway. They've decided that they're going to chase after the inner Tzadik ha-Dor rather than be cowed by it.

What would it mean for you to start trying when you're not sure you can do it? Chad Aboud had a great post on LinkedIn this week that argued perhaps the most valuable skill any of us can learn is the skill of just starting. Trying to do the thing, irrespective of whether you feel prepared, no matter whether you know how to do it.

One of the things that we don't talk about enough is that any meaningful project is fraught with doubt, insecurity, fear – as well as joy, exhiliration, and pride. Every creative endeavor has the risk of not working.

That's what makes it art: the fact that it may not work.

I must be a glutton for punishment, because once I got a taste for taking on these big, hairy projects, I don't want to work on much else. This means existing in an ever-present state of tension, because most everything I'm working on may not work.

But if is does? The moment between release and confirmation of success is when I feel most alive.

How long do you think it's gonna last?

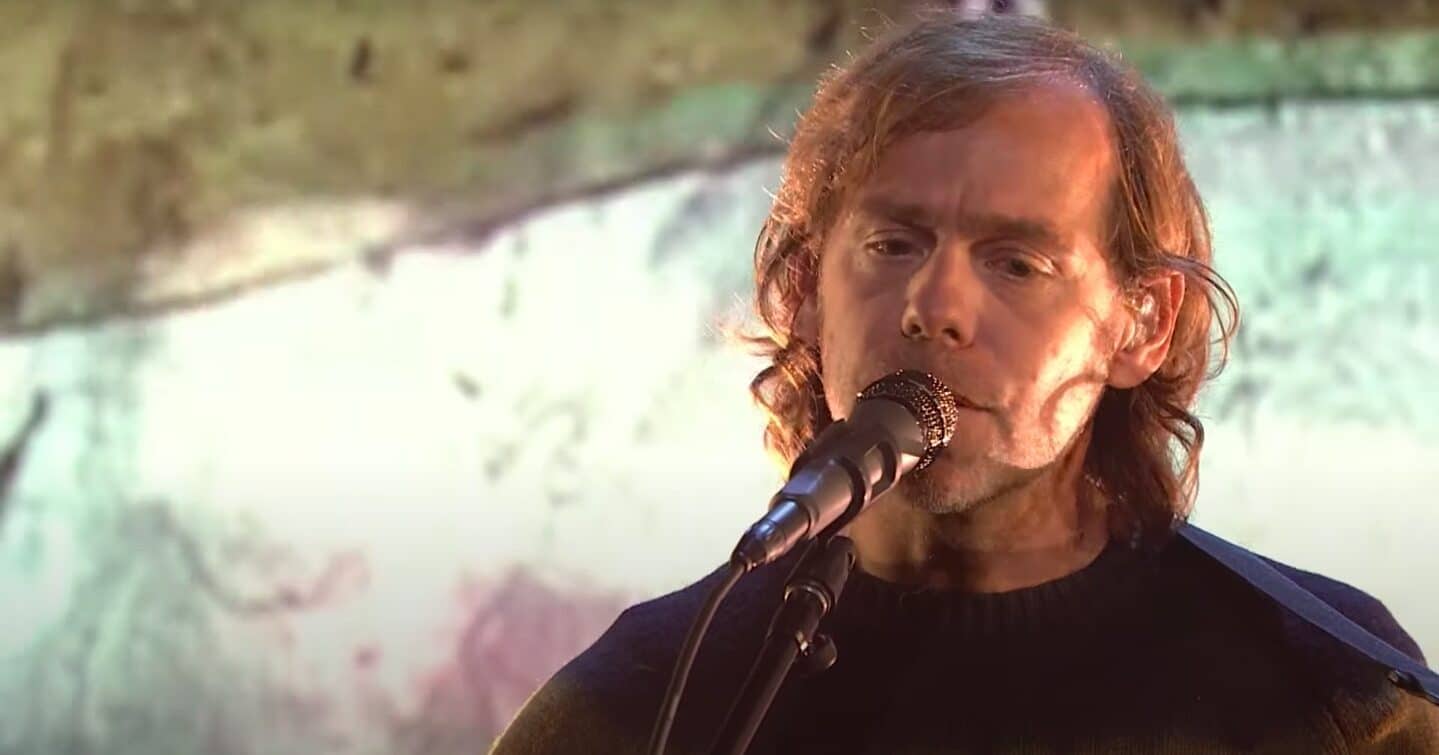

Big Red Machine is likely a band you haven't heard of yet is comprised of people you've definitely heard of. I love this kind of band, as they often serve as a playground for artists to just play without the weight of the names of their day jobs:

The National, Bon Iver, Fleet Foxes, Taylor effin' Swift.

How Long Do You Think It's Gonna Last? is Aaron Dessner's coming out party – which is hard to fathom because of how low-key prominent he's been in so many different projects. He's one of the lead songwriters for The National, a ubiquitous producer, helped write T-Swift's Folklore and Evermore. But it's this album that for the first time puts him out front and center.

Big Red Machine's first album saw Dessner in his usual spaces: playing guitar, piano, writing music, producing. Justin Vernon, of Bon Iver, was the face and voice of the band. But this time around, Vernon insisted that Aaron take center stage. He's written more of the songs and, for the first time, gets behind the mic and lends lead vocals to three songs.

It's as though Aaron kept building on the things he knew how to do: The National, production, etc. He worked behind some of the most iconic voices in music – Matt Berninger, Justin Vernon, Local Natives, Taylor Swift. But there was another piece he knew was inside him. Another uncomfortable step.

With a bit of a push from Vernon, How Long Do You Think It's Gonna Last? is Aaron Dessner walking out, building the muscle to try to do something he doesn't know will work.

And that's what art is.

Member discussion