OTR, Take 51: Count Basie - Basie at Birdland

We live in an age of abundance, and it's made us sleepily arrogant. Our streaming services provide us the illusion of having all of the world's television and music right at our fingertips. Amazon has fooled us into thinking that any book ever written is just a download away. Google has shifted the way we think: we no longer need to know anything, we just need to know how to run a search.

The sheer amount of information available at our beck and call is indeed astonishing. In some ways, there's never been a better time to be an artist. Musicians can record studio quality music on their laptops with the right software and plugins and put it right up on Bandcamp and Spotify. Writers can self-publish. Nearly all of the intermediaries, the arbiters of taste, can be removed from the process.

And yet.

It is, of course, an illusion. I'm all for opening the lines of distribution and removing the A&R asshole, the editor who wants only what he or she wants, the gallery owner who fancies himself a tastemaker as a necessary hurdle in the process to reach people. That's not the issue. The issue is we have this arrogant assumption that removing all of these arbiters of access means everything is accessible.

When I was in high school, I geeked out on music – obsessed over it, devoured it, picked up the guitar so I could create it. After I saw my first live show (my first four shows were Oasis, U2, the Rolling Stones, and Page & Plant, spoiling me rotten), I realized that the albums were one face of the music. The live shows had an entirely different energy, a different aesthetic.

So I started collecting bootlegs of live shows of my favorite bands, trading tapes with people from all over the world (the first moment that I realized how the internet would change the world was when I traded Oasis bootlegs with a guy in Rio). By the end of my senior year in high school, I had well over 500 bootlegged shows from Oasis, U2, the Jam, my bloody valentine, Radiohead, Built to Spill, and Hum. Almost none of the shows I had on tape or CD are available on any streaming service, and most of them are probably lost to time. I don't have my copies, anymore.

But, I hear you object, we have the studio versions! Yes, we do, and we can find those on nearly any streaming service. But to this day, I withhold my fervor for any musician until I can see them live: a studio (or a laptop) can make nearly anyone sound good. On stage, especially a stage like the one above, there's nowhere to hide. It's you, your mates, and the audience. You can either play or you can't. It's about as binary an experience as you get – on both ends of the equation. Even if you can play, you have off-nights, where you let yourself and the crowd down; you have nights that are perfectly good shows; and you have transcendent nights, where some alchemy happens and the music you produce has a magic to it.

Every night is a bit different, and everyone of those tapes revealed a different incarnation of the bands. Songs took on different tones and inflections, the musicians, bored with playing the same fucking parts night after night would freelance, either to the delight or frustration of his bandmates and the crowd.

The easy access to "music" has changed the way we think about it. It's now a fixed thing in our heads, a song being the thing on record, rather than what music has been for the rest of human existence: a unique live performance, often of standard songs that everybody knew. Hell, the last show I went to, the folks behind me were bitching that Jason Isbell wasn't playing the songs exactly the same as they are on the record.

We generally think of jazz, now, as a single thing. Miles and Bird and Basie and Benny and Glen and Louis and Dizzy. We only think this now because we have, mostly, moved beyond it as a dominant art form. But in the same way that we thin-slice rock ("post-rock" and "post-hardcore" and "post-punk" will all sound the same in 50 years, after the culture has moved), there are many different kinds of jazz.

In the 1930s and early 40s, Swing was king. You know this sound, if you let yourself think about it: this sound is defined by Big Bands, rousing melodies, often with lead vocals from names you know well. Count Basie and his Orchestra was one of the finest of these Swing bands.

Originally forming in 1936 in Kansas City, before moving up to Chicago later that year, Basie and his Orchestra had a kick to their sound that nobody else did. Much of this came directly from Basie's piano, which almost never played what you expected; his playing was contrapuntal and, while never attention-seeking, very attention-grabbing in the accents it added to the music.

So many great musicians moved in and out of Basie's Orchestra: Freddie Green, Lester Young, Sweets Edison, Herschel Evans, etc. It was impossible for his band not to be great because he was so much fun to play with, so generous with giving other players space to shine, that Basie drew great musicians into his orbit.

It might be an exaggeration to say that Swing was a pre-War artform and Bebop was the post-War change, but not much of one. Wars are cultural touchstones for many reasons: there's generally a significant loss of young men, destruction of things, and often the dissolution of ideas or worldviews.

American Pragmatism could not have been developed without the utter devastation of the Civil War. Peirce, James, and co. all lived through the Civil War and much of the thinking at the heart of Pragmatism is an attempt to piece together a world that no longer offers stable access to truth and reality. (Peirce is an intellectual hero of mine, but I would be remiss if I didn't say he and his family were casually okay with slavery and he was exempted from military service as he was otherwise serving in the United States Coast Survey, a government scientific endeavor at the time.)

World War I saw the destruction of Europe as it existed. Perhaps no writer captured this better than Ford Madox Ford in his two major works, The Good Soldier, which was written pre-war and published right as the lions of July were roaring, and Parade's End, his four-part masterpiece casually laying bare the destruction of European civilization. We see these ideas in so much of the post-WWI literature and poetry, with the sweet lie laid bare: dulce et decorum est, pro patriae mori.

The Swing sound of pre-WWII jazz sounds to me like a confident country coming into its own, brash, forward, and danceable. Post-war Bebop, though, is something different entirely: a form that had reached maturity, aware of its place in the world, and challenging.

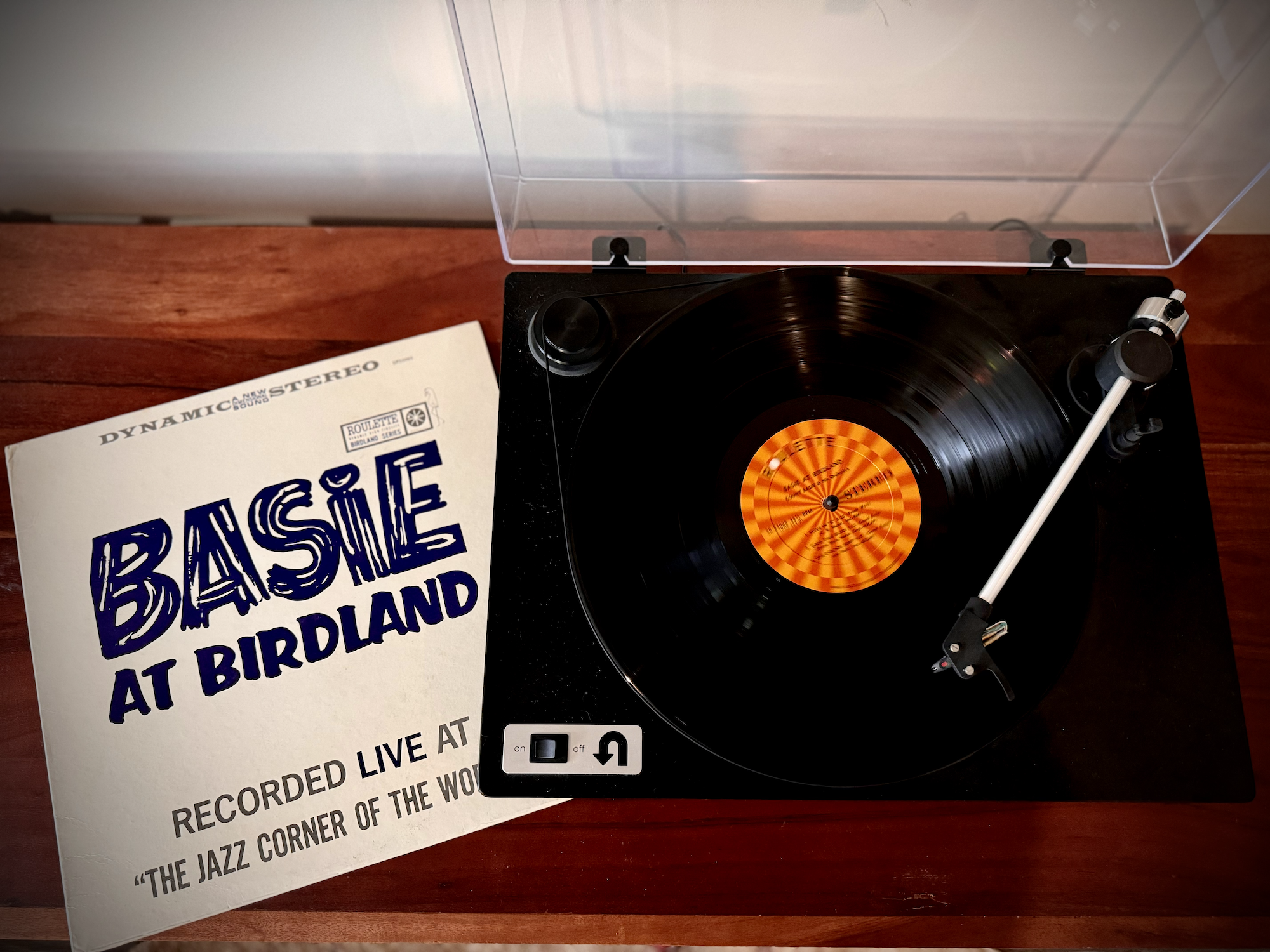

I put on Basie this morning for a few reasons, not the least being that I love this recording. (You can't find this anywhere streaming, so I guess it never happened.) But also because I've been thinking about the move from Swing to Bebop in the context of my novel, Pennhollow. Jazz is, in a way, a character in the book and the cultural move from Swing to Bebop sits at a cultural divide that animates some of the conflict.

I was looking over a passage from earlier in the book last night as I was writing to ensure that what I remembered was in fact what happened. I came across this passage, which I'd forgotten about (it's amazing how much of your own book you forget about...) and it made me want to listen to some Swing this morning to get at the struggle James is having here (the excerpt is marked by dividers):

The bass line stopped his heart, broke it into tiny pieces. The poor muscle was already pumping at capacity, straining to keep up with Lexis, but James thought he’d have a moment to rest between songs. Then the bass kicked in and it was too much to bear.

It was unlike anything he had ever heard – not your standard walking jazz line but an ostinato figure, something with sharp edges and a mission. The bass was at once immensely sad, a melody poking and prodding one’s capacity for melancholy. But it was also insistent: aching though not morose, vacillating between a frantic pace that civilians associated with war and a languid melody that lingered in the fiber of your being. The pattern of half-step chord changes, subtly changing the bass pattern, evoked an eerie, otherworldly sensation.

“Why don’t we sit this one out, James?” Lexis had taken his hand and led him to the edges of the room. She wiped a tear from James’s cheek and he realized for the first time that he was crying. Big, wet tears were streaming down his face and Lexis patiently used the sleeve of her dress to sop them up. “You look like you just missed your best friend’s funeral.”

“I’m – I’m sorry, I don’ know what’s come over me….” He removed his glasses to better rub his eyes.

Although there wasn’t much room for further retreat in the small room, Lexis navigated them to a dusky, smoke-filled corner of the club. The bassist had been playing solo for a minute or two, smiling as the drummer began feeling out his place, what space he needed to fill. With a nod from the bassist, the sax came in hot, contrapuntal to the bass, destabilizing the little bit of solid ground James had found following the base.

“What is this?” His tone was one of honest wonder, trying to comprehend music at once so familiar and yet so fundamentally new.

Next to him, Lexis had stopped dancing – although she never really stopped moving in time with the music – and was tending to James. She was wearing a knee-length full sleeved black dress. James had grown accustomed to the attention that Lexis drew from both men and women, though Lexis seemed to be entirely unaware of the effect she had on a room. Perhaps because she had never known otherwise, James thought the morning after another night out where every door opened to Lexis as if she herself was the skeleton key.

“This, G.I. James, is bop. Serious jazz. It’s amazing, isn’t it?” She took hold of a gin that someone had made appear without, to James’s knowledge, Lexis making any signal for one. As though everybody knew that she could not be trusted alone without a gin lest she failed to make it back to the dance floor.

Can you imagine a world where that bassline would have been edited out by a producer because it wasn't catchy enough? Where the real-time discovery would be mediated by the Spotify algorithm?

We're moving from a world where chance and choice drive human behavior to one where the decisions are made for us, without our full awareness. There are compelling business reasons that Spotify, Amazon, and Netflix want this to be the case. If I owned one of those companies, I would probably be pushing these same things because I'm merely human and will selfishly manipulate systems and situations for my own gain if given the opportunity.

But let's be a bit more cognizant of what it is we're ceding away. So many of the most meaningful moments of my life have been happy accidents, shared moments that happen only once, communal occasions that defy expectation – and moments, sitting alone, reading a book I chose to read or listening to a record that spoke to me in that moment.

Is the algorithm ever going to stop your heart and break it into tiny little pieces?